Most applications are moving to containers because of big benefits this approach gives us: scalability, immutability, efficiency, and so on. But adding abstraction layers could make much more difficult other tasks. One of them could be security.

Today, I would like to imagine a scenario where we have our web server running in a container. It is running smoothly until we detect that we are under a DDoS attack. While our server is under attack, the users can experiment long latencies or even they can’t access to the service. Actually, if the attack is really high for a long period of time, our server could go down.

The first idea that can come in mind is to work with netfilter(iptables). But we would like to have a solution that will perform better and, in this case, will just affect our containerized application. What about eBPF?

eBPF is a revolutionary technology with origins in the Linux kernel that can run sandboxed programs in an operating system kernel. It is used to safely and efficiently extend the capabilities of the kernel without requiring to change kernel source code or load kernel modules (source https://ebpf.io/).

Thanks to eBPF, we will be able to run our programs in the Linux Kernel improving the performance in a considered way. As we are suffering a DDoS attack, whose purpose is to consume server resources, our target would be to drop the attacker’s packets as soon as possible, avoiding to waste our resources which will be ready for our users.

In order to execute our program as soon as possible, it exists a framework called XDP which will allow us to hook our program in the network interface controller (NIC) having the possibility of checking the received packets and deciding if the packet should be dropped or not.

Some tests show how XDP allow us to drop up to 26 million packets per second per core with commodity hardware source

Experiment

Server

Let’s build a simple web server. Firstly we need a index.html

<html><head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

<title>Web Server</title>

</head>

<body cz-shortcut-listen="true">

<h1>Hello !!</h1>

</body></html>The application will run in a user-defined docker bridge network:

$ docker network create mynetwork

8838734f993fNow, we can launch our server:

$ docker run \

--rm \

--name server \

--net mynetwork \

-p 8000:8000 \

-w /html \

-v `pwd`:/html:ro \

python:slim \

python -m http.server Apart from the logs, we can also check the web server through the port 8000:

$ curl localhost:8000

<html><head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

<title>Web Server</title>

</head>

<body cz-shortcut-listen="true">

<h1>Hello !!</h1>

</body></html>Attackers

To simulate a, really small, DDoS attack, we are going to open several shells and we will run the following in each one:

docker run \

--net mynetwork \

--rm \

busybox /bin/sh -c "while true; do /bin/wget -qO- http://server:8000; /bin/sleep 1; done"The attackers will be connected to the same network where the server is, for that reason it will be reachable only using its container’s name, server. The attack will consist in requesting to the server every second (each attacker).

In this moment, the server will show the following logs:

172.29.0.3 - - [17/Oct/2022 14:16:56] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.29.0.3 - - [17/Oct/2022 14:16:57] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.29.0.4 - - [17/Oct/2022 14:16:58] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.29.0.3 - - [17/Oct/2022 14:16:58] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.29.0.4 - - [17/Oct/2022 14:16:59] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -In our case, we have a couple of attackers whose IPs are 172.29.0.3 and 172.29.0.4.

Protector

Our protector code will use the library BCC which will permit to write our eBPF program in C but it provides the possibility of writing our loader in Python. This loader will also have the possibility of interacting with the eBPF program to exchange data.

Firstly, we are going to code the frontend in Python.

interface = "eth0"

b = BPF(src_file="ip_blocking.c")

fn = b.load_func("block", BPF.XDP)

b.attach_xdp(dev=interface, fn=b.load_func("block", BPF.XDP))The first part is related to the loader. We decide in which interface we are going to hook our eBPF program, eth0. There is a code called ip_blocking.c which is the eBPF program, and the callback which will receive the event when a new packet arrives to the NIC is a function called block.

def _ip_to_bin(dotted_ip):

ip = ipaddress.ip_address(dotted_ip)

return ctypes.c_uint(int.from_bytes(ip.packed, "little"))

def _load_cache(dotted_ips):

print("loading IPs...")

cache = b.get_table("cache")

for dotted_ip in dotted_ips:

ip = ip_to_bin(dotted_ip)

print(f"{dotted_ip}: {ip}")

cache[ip] = ctypes.c_char(1) We need a helper functions: _ip_to_bin and _load_cache.

The first one will help us to transform a dotted-string IPv4 address to a little endian binary integer of the IPv4 address that is the format which will be received in the packet.

_load_cache, as its name says, will load into a cache the IP of the attackers. This cache will also be accessed by the eBPF program, giving us a mechanism to communicate between the kernel namespace (eBPF program) and user namespace (frontend written in Python).

def run(ips):

_load_cache(ips)

try:

print("running...")

b.trace_print()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("going out !!")

finally:

b.remove_xdp(interface, 0)run contains the high-level logic:

- Load cache with the given IPs

- Print traces from eBPF program

- Unload eBPF program after finishing

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) == 1:

print("No IPs have been provided")

exit(1)

run(sys.argv[1:])Finally, during the main, we check that there are IPs are arguments and we call run.

Full code:

import ctypes

import ipaddress

import sys

from bcc import BPF

interface = "eth0"

b = BPF(src_file="ip_blocking.c")

fn = b.load_func("block", BPF.XDP)

b.attach_xdp(dev=interface, fn=b.load_func("block", BPF.XDP))

def _ip_to_bin(dotted_ip):

ip = ipaddress.ip_address(dotted_ip)

return ctypes.c_uint(int.from_bytes(ip.packed, "little"))

def _load_cache(dotted_ips):

print("loading IPs...")

cache = b.get_table("cache")

for dotted_ip in dotted_ips:

ip = ip_to_bin(dotted_ip)

print(f"{dotted_ip}: {ip}")

cache[ip] = ctypes.c_char(1)

def run(ips):

_load_cache(ips)

try:

print("running...")

b.trace_print()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("going out !!")

finally:

b.remove_xdp(interface, 0)

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) == 1:

print("No IPs have been provided")

exit(1)

run(sys.argv[1:])Now, eBPF program.

BPF_HASH(cache, unsigned int, char, 128);First step, declaring the cache that we have already talked during the fronted coding.

int block(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data;

void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end;

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

if ((void *)eth + sizeof(*eth) <= data_end) {

struct iphdr *ip = data + sizeof(*eth);

if ((void *)ip + sizeof(*ip) <= data_end) {

if (ip->protocol != IPPROTO_TCP) {

return XDP_PASS;

}

unsigned int address = ip->saddr;

char *value = cache.lookup(&address);

if (value != NULL) {

bpf_trace_printk("blocking %d...\n", address);

return XDP_DROP;

}

}

}

return XDP_PASS;

}block function (the event callback) is very straightforward. It receives a struct xdp_md as argument that, after some casting, we will use to extract ethernet data. Some data length checks are required, especially to avoid compilers complains, and we can proceed to work with the ip data. Blocking logic only affects TCP, so if it the protocol is not TCP, the packet can go on. Then, we can check if the received source address is in the cache. If it is, we drop the packet. Whatever other case allows the packet to go on.

Full code:

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <linux/ip.h>

#include <linux/in.h>

BPF_HASH(cache, unsigned int, char, 128);

int block(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data;

void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end;

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

if ((void *)eth + sizeof(*eth) <= data_end) {

struct iphdr *ip = data + sizeof(*eth);

if ((void *)ip + sizeof(*ip) <= data_end) {

if (ip->protocol != IPPROTO_TCP) {

return XDP_PASS;

}

unsigned int address = ip->saddr;

char *value = cache.lookup(&address);

if (value != NULL) {

bpf_trace_printk("blocking %d...\n", address);

return XDP_DROP;

}

}

}

return XDP_PASS;

}Once that we have the code ready, we only need to execute it. In order to facilitate the task, I have prepared a docker image.

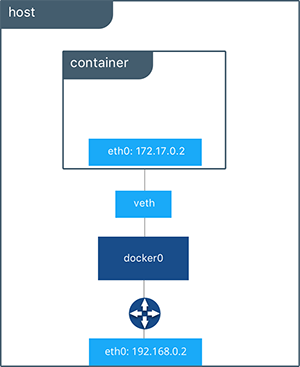

When creating a new container connected to a user-defined bridge network, a pair of virtual network interfaces are created. One in the container and the other one in the host, whose responsibility is just communicating between the different network namespaces.

Protector, which is going to be a docker container, has to have access to the network interface of the server container, so we will connect the container to the server’s network namespace (--net container:server).

docker run \

-it \

--rm \

-v `pwd`:/code \

-v /lib/modules:/lib/modules:ro \

-v /sys:/sys:ro \

-v /usr/src:/usr/src:ro \

--net container:server \

--privileged \

-w /code \

mendrugory/bcc python3 ip_blocking.py <IPs of attackers>This container has to run as privileged and share some directories: /lib/modules, sys and /usr/src. Then, after passing our code through a volume, we can just run it.

Although our code could be added to a custom image, we will use a volume to share it with the container. In that way, we could adapt if it is necessary.

Demo

Code

All the code can be found here.